Triglochinin

Hydrogen cyanide

p-Cresol

Dimethyl trisulfide

Introduction -

Common -

Bacteria -

Plantae -

Angiospermae -

Chromista -

Protozoa -

Fungi -

Animalia -

References

Alismatales -

Liliales -

Zingiberales -

Poales -

Asparagales -

Piperales -

Laurales -

Magnoliales -

Ranunculales

Angiosperms are the largest group of vascular plants. Some of their general compounds are reviewed on that page. Here I have started going through a more detailed look at orders and families. This is still extremely incomplete, and so far only covers some major groups of monocots and only a few dicots. Comments are welcome.

Angiosperms diversified quickly and much of their variation occurs in rather than between lineages. Most orders are based on genetic trees, and while I have tried to give an idea of their common features, these are rarely unique or universal. However many families are more consistent, particularly in terms of floral structure, as noted below.

The orders from Alismatales to Asparagales are monocots, where differentiated seed embryos typically have a single leaf rather than a pair like in most other types. They tend to be herbs with parallel-veined leaves, which often form sheaths around the stem, and have flowers with parts in whorls of three, though there are various exceptions to all these things.

Alismatales have small flowers, often with the perianth reduced or free carpels, and many share distinctive axillary squamules at stem nodes. The leaves are typically sheathing but sometimes net-veined, especially in Araceae which are largely forest plants; the other families are all partly to fully aquatic and sometimes even marine herbs.

Araceae, the arum family, mostly have flowers crowded in fleshy spikes called spadices, each with a prominent and often coloured spathe that encloses it during development. Leaves are bifacial and simple or become compound by perforation. Different types vary from large climbing to small floating plants, including extremely reduced duckweeds.

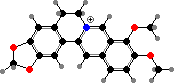

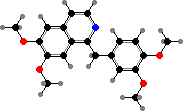

A number of Araceae and Juncaginaceae have triglochinin, one of various cyanogenic glycosides found in different plants, which are broken down by enzymes in damaged tissue to release hydrogen cyanide. This bitter volatile binds to cytochromes and so is toxic to many animals, fungi, and so on, though some specialists can metabolize large amounts.

These also include many examples of flowers with scents that attract scavenging flies and beetles. For instance some Arum are manure mimics, with characteristic p-cresol as well as more common floral compounds like indole. Types like giant Amorphophallus that mimic decaying meat have sulfur compounds like dimethyl di- and trisulfide.

Liliales are largely herbs with soft parallel-veined leaves or else, in Smilacaceae, climbing plants with net-veined leaves and tendrils. Most have flowers with 6 tepals and stamens, the former often all petaloid, and a 3 locule ovary, usually superior to other parts. The seeds store oils and protein over starch and lack phytomelanin as found in Zingiberales and Asparagales.

Dioscoreales, Liliales, and Asparagales often have saponins in the form of steroid glycosides. These are soap-like, readily foaming in water and affecting membranes. Typically leaves have inactive bidesmosides while parts like roots or seeds have monodesmosides, which are antifungal, usually bitter or irritating on ingestion, and also very toxic to animals with gills.

In these orders bidesmosides are based on furostanols, combined with various oligosaccharides plus a stabilizing glucose unit. When this is removed, for instance upon injury, they rearrange into corresponding monodesmosides based on spirostanols. Glycosides of diosgenin and its furostentriol precursor shown are common representatives of these types.

Some Melanthiaceae also have steroidal alkaloids, for instance cyclopamine in Veratrum californicum, noted for causing fatal birth defects in sheep. Colchicaceae like Colchicum (autumn crocus) typically have colchicine, a toxin preventing microtubule formation in cells, which in small amounts is used as an anti-inflammatory to treat gout.

Zingiberales have broad leaves with a sheath, stalk, and midrib giving rise to parallel secondary veins. The flowers show bilateral symmetry or form mirrored pairs; each has 6 tepals in unlike whorls, but usually only 1 or 5 fertile stamens, accompanied by sterile and often petal-like staminodia. Most are tropical herbs, though some are large and tree-like.

This is one of a few orders with diarylheptanoid compounds, most in Zingiberaceae but also precursors for phenalenones like anigorufone in Strelitzia and Musaceae. The latter are photoxic pigments, some formed only in response to infection, also found in the nearby family Haemodoraceae where they colour parts like roots red.

Zingiberaceae, the ginger family, are aromatic with ethereal oil cells in all parts. They have symmetrical flowers with differentiated sepals and petals, and typically 2 outer and 2 inner staminodia, or occasionally just the latter pair. These two make up a whorl with the single fertile stamen and are united to form a petaloid lip or labellum.

The best known diarylheptanoid here is curcumin, a yellow antifungal pigment in rhizomes of Curcuma like turmeric, used as both spice and dye. There are also related phenols like gingerol, which along with degradation products gives Zingiber (ginger) their pungent taste, while the volatile oils are largely terpenoids.

Poales have seeds storing mainly starch grains, shared with Zingiberales, and typically parallel-veined leaves. Flowers in some families have 3 sepals and 3 petals, but in others all the tepals are dry and chaffy, or they have at most a vestigial perianth and occur in spikes or spikelets. These reductions mostly go with wind- or sometimes self-pollination.

Poaceae, the grasses, have inflorescences in spikelets of small flowers; each occurs in the axil of a scale-like lemma and has other scales for its perianth, often persisting around the 1-seeded fruit. Most have hollow stems and open-sheathed leaves in two ranks. They vary from herbs, dominating vast grasslands where trees are limited, to tall woody bamboos.

Leaves here grow from the base and most endure grazing well, but even so have deterrents like silica bodies. Some grasses are cyanogenic, for instance bamboo shoots and many chloridoids. The main glycoside is taxiphyllin, also accumulated in a few conifers as well as other angiosperms; Sorghum have its stereoisomer dhurrin.

Many poöids and panicoids including wheat and maize have benzoxazinones like DIMBOA, again stored as glucosides and released in damaged tissue as well as from roots. The free forms are unstable and reactive, gradually degrading into benzoxazolinones and formic acid, and toxic to various fungi, insects like aphids, and other nearby plants.

Asparagales include both herbs and woody plants, with leaves again mainly parallel-veined though variously soft, tough or succulent, or reduced to absent. Most flowers have 6 tepals, often all petaloid, and 6 or fewer stamens. The seeds do not store appreciable starch and many have an outer coat of phytomelanin, absent mainly in Iridaceae and Orchidaceae.

Amaryllidaceae, the amaryllis family, are herbs with bulbs or rarely rhizomes. They typically have inflorescences of compact cymes, often umbel-like though in some reduced to single flowers, on stems with an involucre of usually 2 membranous bracts. Some flowers have a petaloid corona in addition to the tepals.

Allioids have a characteristic scent from defensive sulfur compounds. For instance Allium sativum (garlic) produce alliin, on damage broken down into thiosulfinates and then volatiles like diallyl disulfide. A. cepa (onions) also have isoalliin which forms propanethial S-oxide, a gas causing tears. Saponins occur in flowers and fruits.

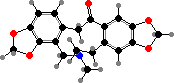

Amarylloids, which have inferior ovaries, lack both these types of compounds; instead most have a unique family of alkaloids sharing norbelladine as a common precursor. Among these, galanthamine from Galanthus, Narcissus, and others is a cholinesterase inhibitor notable for medical use treating symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Asparagaceae are a diverse group including some woody plants, types with reduced leaves, and more typical herbs. Flowers usually have superior ovaries with nectaries, and seeds phytomelanin, but these vary. Most scilloids have bulbs while others form pollen by successive division of mother cells, both rare in relatives save Amaryllidaceae.

Saponins are abundant here. There are also some genera with cardiac glycosides, toxins that affect muscle contraction and in particular disrupt or arrest heart activity. These are based on cardenolide or bufadienolide steroids, each with a characteristic lactone side chain; convallatoxin in Convallaria and scilliroside in Drimia are examples of the two sorts.

Piperales are herbs or smaller woody plants, most aromatic with ethereal oil cells. Flowers typically have both stamens and carpels but reduced or no petals. In Aristolochiaceae the sepals form a distinctive tube above the ovary, while in Piperaceae and Saururaceae there are none and the flowers are crowded in spikes.

This is one of a few orders that have benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, with norcoclaurine as a common precursor. Here for instance Aristolochia (birthworts) usually have derived aristolochic acids, toxins noted for causing kidney damage and cancers, which are also taken up by some swallowtail caterpillars.

The ethereal oils are largely common terpenoids but some Asarum and Piper have more phenylpropanoids, notably safrole, also typical of some Laurales and Schisandraceae. This has a root beer scent and sources like P. auritum or sassafras are used for flavouring, but now regulated as a likely carcinogen and the precursor for the synthetic drug Ecstasy.

Piperaceae, the pepper family, have minute flowers with 2-6 stamens and an ovary containing a single basal ovule. The leaves are usually alternate but may be opposite or whorled, and the fruits are berry- or drupe-like. They are typically tropical or subtropical and some are succulent or epiphytes.

Piper commonly produce defensive amides from phenolic or other precursors, most notably piperine, which is responsible for the sharp taste in fruits of P. nigrum (black pepper) and others used as spices. The Pacific species P. methysticum also has sedative lactones like kavain, mainly in roots, used for the Polynesian drink kava.

Laurales are nearly all woody plants with ethereal oil cells. Many have unisexual flowers; the carpels where present are separated or single, with ovaries inferior to the other parts or surrounded by a raised hypanthium. The pollen mostly have no apertures, less often two, and are commonly released through longitudinal valves instead of the more usual slits.

Lauraceae, the laurel family, have small flowers with tepals in 2 similar whorls on a hypanthium. The stamens usually occur in 3-4 whorls with the innermost often replaced by sterile staminodia. The fruits are drupes or berries, sometimes enclosed by the hypanthium, with a single seed and large embryo. Most have alternate leaves with translucent dots.

Ethereal oils in Cinnamomum and relatives are notable for phenylpropanoids like safrole, eugenol, and cinnamaldehyde; the last gives the sweet-spicy flavour of cinnamon bark. Some others used for fragrances or flavouring include C. camphora with camphor, Aniba with (–)-linalool, and leaves from Laurus nobilis (bay laurel) with 1,8-cineole.

Persea americana (avocado) are unusual for very large seeds and fruits best suited to dispersal by larger mammals. Such types are often protected from smaller organisms, in this case by persin, also found in leaves and bark. This is antifungal and although the levels in the pulp are safe for humans, they can be harmful to many smaller mammals and birds.

Magnoliales are again nearly all woody with ethereal oil cells. The carpels are separated or single with superior ovaries, and when multiple are typically arranged in a spiral along with many stamens, often forming an aggregate fruit. The pollen most often have a single aperture, rarely none or two.

Annonaceae, the custard-apple family, mostly have flowers with 3 sepals, 6 petals in two whorls, and many short stamens where the connective tissue is prolonged and often enlarged above the anther. The fruit are usually fleshy with a small stalk. All are tropical or subtropical except Asimina in North America.

Here parts like leaves, roots, and seeds often have distinctive acetogenins with γ-lactone groups. Malmeoids where known mostly have acetylenic kinds like mitregenin in Mitrephora, while annonoids mostly have C35 or C37 kinds like annonacin in Annona and Asimina. These act as protective toxins interfering with cellular respiration.

Ranunculales are eudicots, with triaperturate or derived pollen. They grow as herbs, vines, or shrubs with mostly alternate leaves, often compound or dissected and lacking oil cells. Flowers usually have more than one whorl of petals and at least as many stamens, or else in Ranunculaceae tend to be partly to fully spiral, and in most families have free carpels.

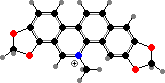

Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids are nearly absent in other eudicots but especially common and diverse here. A widespread example is berberine, a yellow antimicrobial found in many different genera like Chelidonium, Berberis, and Coptis. This often gives colour to parts like roots or latex and has been used by various peoples for dye as well as medicine.

Saponins are also scattered in several families here and among eudicots in general. In contrast to monocots, in most orders these are glycosides of C30 terpenoids rather than steroids; oleanolic acid and derivatives are the most common. These types are less strongly antifungal but more active against other organisms like bacteria.

Papaveraceae, the poppy family, are mainly herbs with latex or secretory cells. The flowers have parts in whorls of two or sometimes more, and unlike relatives have compound ovaries, typically with ovules on parietal placentas and becoming capsules though both vary. Most have stamens in many whorls, the outer maturing first, or in two bundles of three.

This family typically have alkaloids like protopine and derivatives where the benzylisoquinoline structure is altered, notably sanguinarine in roots, stems, and leaves of many different genera. This is antimicrobial and toxic to cells in general, with sources like Argemone seeds noted for causing epidemic dropsy and glaucoma.

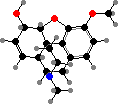

Latex from Papaver somniferum capsules, called opium, has been used as a painkiller for all recorded history. Morphine is the main alkaloid responsible for its narcotic effects, targeting endorphin receptors. Its precursor codeine is also used, while the minor alkaloid papaverine is used as an antispasmodic drug.